Consider That It's A Bit

It's Good For You!

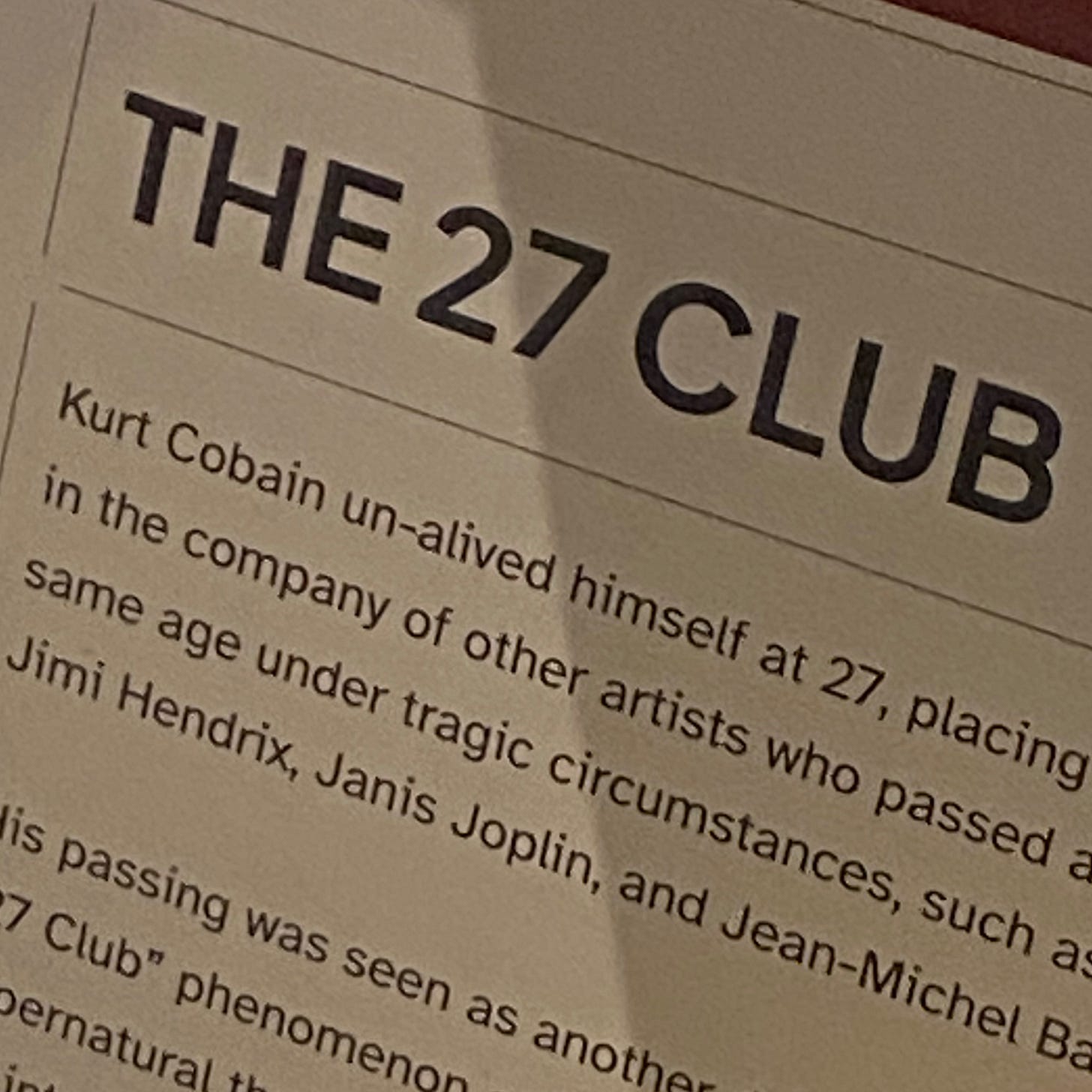

The Nirvana exhibit in Seattle refers to Cobain’s suicide as “un-alive”ing himself.

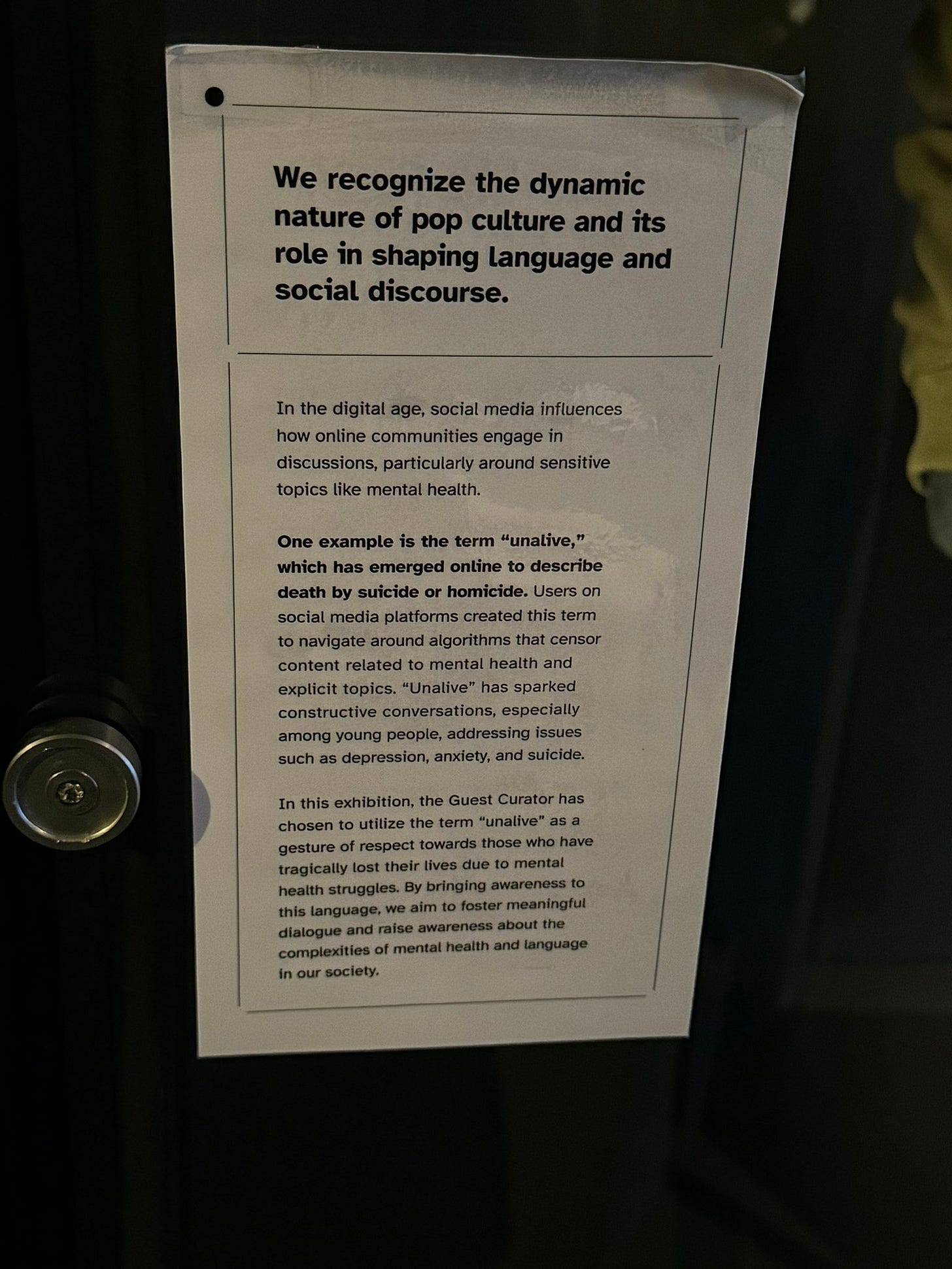

Seems ridiculous, since the censorship that caused cowards to use the un-alive term rather than “suicide” is entirely online and doesn’t apply to a museum in real space that controls the physical objects on its property. Fortunately a placard nearby says that this is exactly why they’re doing it.

Very cool that they’re drawing attention to the online censorship in such an attention-grabbing way!

But the best part is the final paragraph of the placard, which says they’ve “chosen to utilize the term “unalive” as a gesture of respect towards those who have tragically lost their lives” and they wish to “foster meaningful dialogue and raise awareness”.

This is, of course, the language of the censors. Which means these two placards are themselves a brilliant piece of satirical art.

Let me draw an analogy to Andy Kaufman.

Man On The Moon

Kaufman died before I could speak English, and I’ve never seen anything he was in (though I keep hearing I should watch Taxi). Literally 100% of what I know of him is from the biopic Man On The Moon, and biopics are infamously inaccurate. Fortunately for Kaufman this doesn’t matter.

According to what I remember of the movie (which I saw 15 years ago when it came out, so at this point this is almost the only thing I remember), Kaufman’s whole deal was committing to the bit. Committing so hard and so thoroughly that it was impossible to believe he could be committing to a bit. And yet there he was, committing to the bit regardless. His comedy was more often for himself than for his audience — he did it to see the reaction of an audience to someone committing to something beyond all scope of reason. And for everyone else who was also interested in seeing what an audience’s reaction to someone committing so hard will be.

Imagine Borat, except he’s living as Borat, and doing his best to convince everyone that he really is Borat, and you only get the joke if you believe that despite seeing an IRL Borat in front of you, no one could actually be Borat, and this must be a bit. That was what Kaufman tried to pull off. You only get the joke if you disbelieve what you are being presented with.

This leads to one of the most beautiful climaxes of the comedian biopic genre. Kaufman, dying of cancer, flies to South America for treatment from a faith-healer. The shaman (or priest, or something) will use his faith-magic to reach into Kaufman’s body and remove the cancer with his hands. The shaman pokes at Kaufman’s abdomen, palms some chicken guts in a standard slight-of-hand magic trick, and declares him healed.

The movie shows Kaufman realizing this on the operating bed AS IT IS HAPPENING. He knows exactly what the shaman just did. Kaufman starts laughing, and crying, in the most beautiful display of emotion. Because he gets it. He gets the joke. The shaman is doing the same thing Kaufman was doing this whole time. He was fully committing to the bit. And Kaufman recognizes a fellow master, and finds it hilarious, and he can’t even complement him because that would give up the game. And also, now he’s going to die. But he can’t even complain because the bit was just so good.

The infinite-mirror of humor and appreciation and tragedy is heart-wrenching and weirdly uplifting at the same time. Kaufman’s entire life was an extended piece of performance art, and now he’s dying in the most perfect recapitulation of that art, and it’s the most appropriate ending in the world.1

Committing To The Bit As Art

Erik Hoel argues that the universe suddenly hates satire. He makes a good point, but this doesn’t mean satire is impossible, it’s just much harder nowadays. Before you could just exaggerate a normal situation and it was satire. Now everything is exaggerated by default. To really satirize something you have to go deep. You have to fully reflect the thing in all its unholy fullness. That means going further than any reasonable person could expect to go.

Do you really want to mock censorship in The Year of Our Lord 2024? Do you really want people to think “omg, that’s actually fucked up”? You can’t just say “we’re using this term ironically” in explanation. That’s 90s level satire. That’s the satire of a little baby. You have to inhabit what you mock. You have to trust your audience to make their roll to disbelieve, and accept that some of them will fail.

There is a special wonder to going full Kaufman. To commit so hard that even realizing it's a bit is an artistic act. This makes it a collaborative art piece. The audience isn’t just receptive and reactionary. The audience must make a judgement call, and that judgement call is itself part of the art.

And what if the original artist of the Nirvana exhibit really was a soul-dead victim of the newspeak? Does that change the art piece in any way? Does it make it less satirical? This is the importance of the Death of the Artist. The audience interpretation is more important than the artist’s intent. The piece may be satire due to artistic genius or just by accident, but it’s fantastic satire nonetheless.

Consider that this is a bit. Consider that of far more things than you’d naively assume. Your life will be better for it. :)

Though of course only for Kaufman. All the normal people who weren’t living their lives as performance art didn’t deserve this fate, and that shaman should be tried for the murder of everyone except for Kaufman.

Much like your review of The Terraformers, I am impressed by your ability to see this type of thing as satire. I am not entirely convinced that this is the intention of the creators, but the world where you are correct sounds superior to the alternative.